How cheese is made

Cheese isn’t just an ingredient; it’s history, culture, and science wrapped into one glorious bite. Humans have been making cheese for over 7,000 years, and though methods have evolved, the 'how cheese is made' basics remain the same.

Legend has it that cheesemaking began by accident when milk was carried in animal stomachs, where natural enzymes (rennet) curdled it. Instead of tossing it, curious humans tasted the curds…and the rest is delicious history.

Today, different types of cheese are made everywhere: gooey Brie in France, stretchy Oaxaca in Mexico, crumbly feta in Greece, and sharp cheddar in England. And while flavors differ, the process behind them is universal.

The science behind how cheese is made 🔬

Whether it's burrata or mozzarella, ricotta or cottage, or cheddar, or parmesan, the science of how cheese is made revolves around the transformation of milk through chemistry and microbiology. Proteins, primarily casein, coagulate to form curds, while fats and water are distributed within this matrix.

Lactic acid bacteria ferment lactose into lactic acid, lowering the pH and helping curds set, while rennet enzymes further stabilize the structure. During aging, enzymes and microbes break down proteins and fats, creating the complex flavors, textures, and aromas we associate with different cheeses, including sharp vs. mild.

Every step, from coagulation to ripening, is guided by precise chemical reactions that turn simple milk into hard cheeses, fresh cheeses, different types of blue cheese, and more.

Cheesemaking is fermentation. Microbes + enzymes = transformation:

Proteins → savory amino acids.

Fats → buttery, fruity, funky flavors.

Moisture levels → texture from crumbly to creamy.

Microbial activity → bloomy, blue, or washed-rind funk.

In this guide, we’ll walk you through exactly how cheese is made, step by step, so you can better appreciate the science (and the art) that goes into every bite.

1. Milk – The foundation of every cheese

Before we get into curds, whey, and all the quirky science that transforms liquid into a block of creamy goodness, let’s set the record straight: milk is the foundation of cheese. Every wheel, wedge, or slice you’ve ever enjoyed owes its existence to this single ingredient.

The type of milk, cow, goat, sheep, or even buffalo, shapes everything from flavor to texture. Think of it as the canvas on which cheesemakers paint their masterpiece. Without milk, cheese simply wouldn’t exist.

Types of milk used in cheesemaking

Cow’s milk: Mild and versatile—perfect for Cheddar, Gouda, and Brie.

Goat’s milk: Tangy, grassy, and easier to digest for some.

Sheep’s milk: Rich, fatty, and full-flavored. Think Manchego or Roquefort.

Buffalo milk: Creamy and indulgent, used for authentic Mozzarella di Bufala.

Rare types: Yak, camel, and even moose milk cheeses exist (and cost a fortune).

Seasonal milk makes a difference 🌱❄️

Seasonal milk plays a significant role in cheese making because the quality and composition of milk change throughout the year.

Variations in an animal’s diet, influenced by fresh pasture in spring and summer versus stored feed in winter, affect the milk’s fat, protein, and flavor profile. These differences can impact the texture, richness, and taste of the resulting cheese, making some cheeses uniquely tied to specific seasons.

Spring milk: Fresh, floral notes from green pastures.

Winter milk: Richer, nuttier flavors from hay-fed diets.

2. Starter cultures - The flavor engineers 🦠

The starter culture process involves adding specific bacteria to milk at the very beginning of cheese making. These bacteria ferment lactose into lactic acid, which helps acidify the milk, encourages curd formation, and begins developing the flavor and texture of the cheese. Starter cultures are essential for giving each cheese its unique taste profile.

Types of Cultures

Mesophilic: Thrive at moderate temps. Used in Cheddar, Brie, and Camembert.

Thermophilic: Love heat. Perfect for Swiss, Parmesan, and Mozzarella.

Wild cultures: Some makers rely on local, airborne microbes for unique “terroir.”

3. Coagulation: Curds and whey are born 🧪

Coagulation is the stage where liquid milk begins its transformation into solid curds. By adding rennet (an enzyme) or certain acids, the proteins in milk (mainly casein) bind together, trapping fat and water in a gel-like structure.

This is what separates the curds, which will become cheese, from the liquid whey. The firmness of the curd at this stage plays a big role in determining the texture and style of the final cheese.

What makes milk curdle?

Cheesemakers add a coagulant to separate milk solids from liquid whey. Milk curdles when its proteins clump together, which happens when rennet or acids lower the milk’s pH. This change causes casein proteins to bond and form curds, leaving behind the liquid whey.

Traditional rennet: Enzymes from calf stomachs.

Vegetable rennet: Plant-based, made from nettle or thistle.

Microbial rennet: Lab-grown, widely used today.

Acid methods: Vinegar or lemon juice - great for ricotta or paneer.

4. Cutting, cooking & stirring – shaping texture 🔪🔥

Once the curds form, they’re cut into smaller pieces to release more whey and control the cheese’s moisture level. The curds are then gently cooked and stirred, which helps them firm up and develop their final texture.

The size of the cuts, the temperature, and the amount of stirring all play a key role in determining whether the cheese turns out soft and creamy or firm and aged.

Why curds are cut

Curds are cut to release whey trapped inside, which helps control the moisture content of the cheese. The size of the curd pieces directly affects the final texture; smaller cuts make a drier, firmer cheese, while larger cuts keep it softer and creamier.

Small curds: Less moisture → firm cheeses like Parmesan.

Large curds: More moisture → creamy cheeses like Brie.

5. Molding, pressing & salting – From curds to cheese 🧱🧂

After the curds have been cooked and stirred, it’s time to give the cheese its form and flavor. This stage involves molding and pressing the curds into their final structure, followed by salting to enhance taste and help preserve the cheese.

Shaping the cheese

Shaping is the step where curds are gathered and pressed into molds to create the cheese’s signature form. The molds not only determine the size and shape but also help expel excess whey as gentle or heavy pressure is applied.

This process sets the foundation for everything from small, delicate rounds to massive wheels of cheese.

Pressing the curds

Pressing is used to firmly pack the curds together, pushing out additional whey and giving the cheese a solid, uniform texture.

The amount of pressure and time applied can vary widely; light pressing keeps a cheese soft and moist, while heavier pressing creates dense, firm cheese varieties that can be aged for months or even years.

Salting for flavor & preservation

Salting cheese serves a dual purpose: it enhances flavor and helps preserve the cheese by inhibiting the growth of unwanted bacteria. Salt can be added directly to the curds or applied to the surface, and it also helps draw out moisture, which contributes to the cheese’s texture and longevity.

Dry salting: Rubbing the surface.

Mixing salt in: Even distribution.

Brining: Soaking in saltwater (used for Feta, Mozzarella).

6. Aging & ripening – Time works its magic ⏳

Aging, or ripening, is the stage where cheese develops its distinct flavor, aroma, and texture over time. During this process, naturally occurring bacteria and enzymes continue to break down proteins and fats, transforming the curds into a more complex and flavorful product.

The environment, temperature, humidity, and even the type of surface the cheese rests on play a crucial role in determining the final character of the cheese, whether it’s a soft, creamy delight or a firm, sharp masterpiece.

How long does cheese age?

The aging, or maturation, time of cheese can vary widely depending on the type and style. Fresh cheeses may be ready to eat within hours or days, while semi-hard cheeses like Gouda or Cheddar often age for several months to develop deeper flavors.

Hard, aged cheeses such as Parmigiano-Reggiano or Pecorino can mature for a year or more, sometimes even several years, allowing complex flavors, firmer textures, and rich aromas to fully develop. The aging period is carefully controlled to achieve the desired taste and consistency.

Fresh cheeses: Ricotta, cream cheese, paneer - ready in hours.

Short aging (weeks to months): Brie, Camembert, Havarti.

Medium aging (6–12 months): Manchego, Gouda.

Long aging (1–3+ years): Parmigiano Reggiano, aged Cheddar, Comté.

Rind types – Cheese’s outer personality

Cheese rinds come in a variety of types, each contributing to the flavor, texture, and appearance of the cheese. Natural rinds form when the surface of the cheese dries and develops molds or yeasts during aging.

Washed rinds are regularly treated with brine, wine, or beer, creating a strong aroma and distinctive orange hue. Bloomy rinds, like those on Brie or Camembert, are soft and white, formed by specific molds that give a creamy texture just beneath the surface. Each rind type not only protects the cheese but also adds its own unique character to the final product.

Different kinds of cheese rinds

Natural rind: Simply dried surface, e.g., Tomme.

Bloomy rind: White mold coating, e.g,. Brie, Camembert.

Washed rind: Bathed in brine, beer, or spirits - pungent but delicious.

Wax rind: Protective seal, e.g., Gouda, Edam.

No rind: Fresh cheeses like cream cheese or ricotta.

Fresh vs. aged cheese ⏱

Cheeses can generally be divided into fresh and aged varieties, each offering distinct flavors and textures. Fresh cheeses, like ricotta or queso fresco, are soft, mild, and typically enjoyed soon after production.

Aged cheeses, on the other hand, like Cheddar or Parmigiano-Reggiano, are matured over weeks, months, or even years, developing stronger flavors, firmer textures, and more complex aromas.

Fresh cheeses

Fresh cheeses are soft, mild, and often moist, and are enjoyed soon after they are made. They typically have a creamy texture and a delicate, slightly tangy flavor. These types of cheeses go great with certain wines and food, which you can learn about in our cheese pairing guide.

Examples of fresh cheeses:

Ricotta

Queso fresco

Mozzarella

Mascarpone

Cream cheese

Labneh

Aged cheeses

Aged cheeses are matured over time, allowing flavors to deepen and textures to firm up. The aging process develops complex aromas, sharper tastes, and often a crumbly or dense consistency.

Examples of aged cheeses:

Cheddar

Parmigiano-Reggiano

Gouda (aged)

Gruyère

Pecorino Romano

Comté

All about cheese mold 🧀

Cheese mold might sound scary, but in many cases, it’s an essential part of creating flavor, texture, and character. Certain molds are intentionally added to cheese varieties, such as Brie, Camembert, and blue varieties like Roquefort or Gorgonzola.

These molds help break down fats and proteins during aging, giving the cheese its creamy consistency, distinctive veining, and complex, tangy flavors.

Not all molds are edible, though some cheeses develop natural rinds with harmless molds that contribute to aroma and appearance, while others must be trimmed before eating. Understanding the role of mold in cheese helps you appreciate the science and artistry behind each wedge, turning what might seem like an imperfection into a culinary delight.

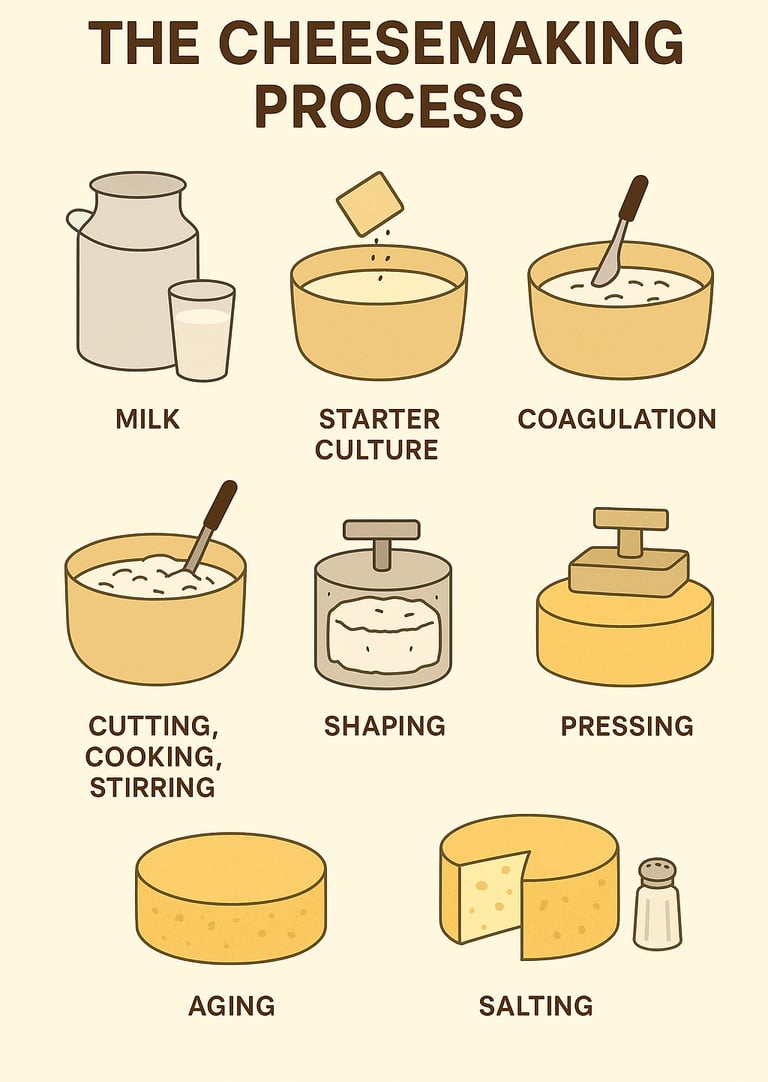

How is cheese made? Quick recap 📋

Milk selection

Add starter cultures

Coagulation (curds + whey)

Cut, cook, stir curds

Mold, press, salt

Age or enjoy fresh

Eat (the best part)

Final bite

From the humble splash of milk to the rich, flavorful wheel on your plate, cheese is a testament to patience, precision, and a little bit of magic.

Whether you savor a fresh, delicate ricotta or a bold, aged blue, every bite carries the story of careful crafting and centuries of tradition. So next time you unwrap a wedge, take a moment to appreciate the art behind the cheese; it’s more than food, it’s a delicious masterpiece.

How cheese is made FAQ

How is cottage cheese made?

Cottage cheese is made by adding an acid or rennet to warm milk, which causes it to curdle and form soft curds. The curds are then drained but not pressed, retaining some of the whey to maintain moisture. Finally, cream or milk is often mixed in to give it a creamy texture.

How is cream cheese made?

Cream cheese is made by blending milk and cream, then adding lactic acid bacteria to thicken the mixture and create a mild, tangy flavor. The curds are heated and whipped until smooth, giving cream cheese its signature creamy texture. It’s then cooled and packaged for spreading or baking.

How is blue cheese made?

Blue cheese is made from cow’s, sheep’s, or goat’s milk and aged with cultures of Penicillium mold, which create its distinctive blue veins. The cheese is pierced with needles to allow air in, which helps the mold grow throughout. This process gives blue cheese its sharp, tangy flavor and crumbly texture.

How is American cheese made?

American cheese is made by blending natural cheeses, often cheddar or Colby, with emulsifiers, milk, and sometimes cream. This mixture is heated and processed until smooth, which creates its mild flavor and creamy, melt-in-your-mouth texture. It’s then cooled and packaged, ready for sandwiches or cooking.

Cheese Soul

Explore the world of cheese and lifestyle.

© 2025. All rights reserved.